The Fed’s hawkish attempts to stem inflation have led to a shift across the global business community. Companies that rode the long wave of easy money up after the Global Financial Crisis—increasing leverage on their balance sheets at a relatively low cost—may soon find themselves beached as the tide turns.

Already, we’re seeing indications of a more prolonged credit downturn that may leave certain companies exposed and in turn, potentially generate a set of stressed and distressed credit opportunities that may be larger, more persistent and more nuanced than what we have witnessed since the Global Financial Crisis.

We continue our ongoing series by analyzing key economic and business factors that may denote the current state and potential trajectory of the credit cycle. We then examine the accumulation of leverage during the post-GFC era and the potential opportunities in the credit market as the cycle progresses.

Business and Economic Cycles Start To Turn

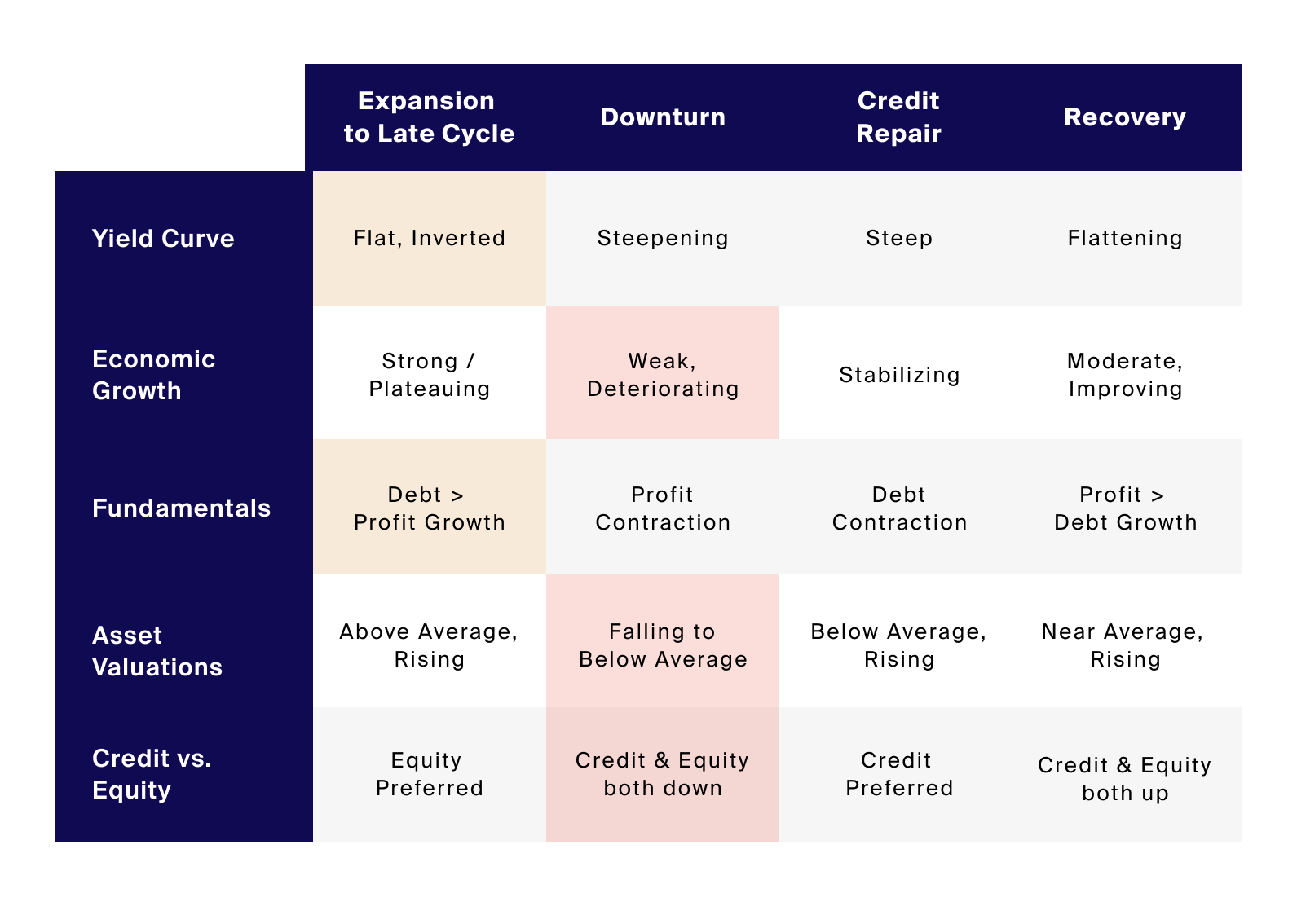

In our last piece, we highlighted how inflation, tightening monetary policy, and deteriorating liquidity and credit growth seem to indicate that the credit market is in a late-cycle to early-downturn phase. Other economic indicators, like the yield curve, GDP growth rate, business fundamentals and asset valuations likewise appear to reinforce these signals (Exhibit 1).

Source: Loomis Sayles, Unlocking the Credit Cycle – December 2019; Bloomberg, Yield Curve represented by 10-Year Treasury Yield minus 2-Year Treasury Yield with ”Flat, Inverted” indicated by a zero or negative latest value. Economic Growth represented by US Real GDP (QoQ % SAAR) with ”Weak, Deteriorating” indicated by negative trend over most recent 12-month period. Asset Valuations represented by S&P 500 Price-to-Earnings Ratio with ”Falling to Below Average” indicated by a negative trend over the most recent 12-month period and last value below the ten-year average. Credit vs. Equity represented by the S&P 500 Index and the Bloomberg U.S. Total Corporate Total Return Index with ”Credit & Equity both down” indicated by negative trends for both indicators over most recent 12-month period. All latest values as of 10/14/2022. Charles Schwab, Earnings Trampled Under Foot, Fundamentals indicated by S&P 500 earnings estimates with ”Debt > Profit Growth” represented by decreasing earnings growth over most recent 12-month period, as of 9/19/2022.

In our last piece, we highlighted how inflation, tightening monetary policy, and deteriorating liquidity and credit growth seem to indicate that the credit market is in a late-cycle to early-downturn phase. Other economic indicators, like the yield curve, GDP growth rate, business fundamentals and asset valuations likewise appear to reinforce these signals.

It’s worth noting that although the indicators we highlight appear to signal a credit cycle downturn, as well as a looming recession, the U.S. economy has appeared resilient to date. In particular, the labor market continues to be relatively tight; the unemployment rate returned to 3.5%—a five-decade low—in September 2022.1 We believe such conditions may encourage the Fed to continue increasing rates until demand cools enough to curb inflation.

Despite job market strength, recessionary signals seem to have appeared elsewhere in the economy. Consider the yield curve, for instance. Economists have historically relied upon the yield curve as a leading recession indicator, as inverted yield curves have correctly signaled the past 10 recessions.2 Since July, the yield curve has become increasingly inverted, with the yield for the 10-year Treasury falling to 50 basis points below the 2-year Treasury, as of mid-October 2022.3 In addition, hopes for growth in the manufacturing sector were dampened in September, with the Institute for Supply Management’s Manufacturing PMI (Purchasing Managers Index) dropping to the lowest value since May 2020 and closing in on the 50-point mark that separates expansion and contraction.4 Though Q3 2022 data reporting is not yet complete, we also think it’s reasonably likely that corporate earnings will be similarly impacted by the combination of higher interest rates and eventual slowing demand. According to FactSet, if the earnings growth rate for the S&P 500 matches estimates at 2.4%, it would mark the lowest rate since the pandemic-induced decline in Q3 2020.5 Furthermore, equity valuations have already fallen; P/E multiples are now compressed below both 5-year and 10-year averages.6

Company Balance Sheets May Be Tested

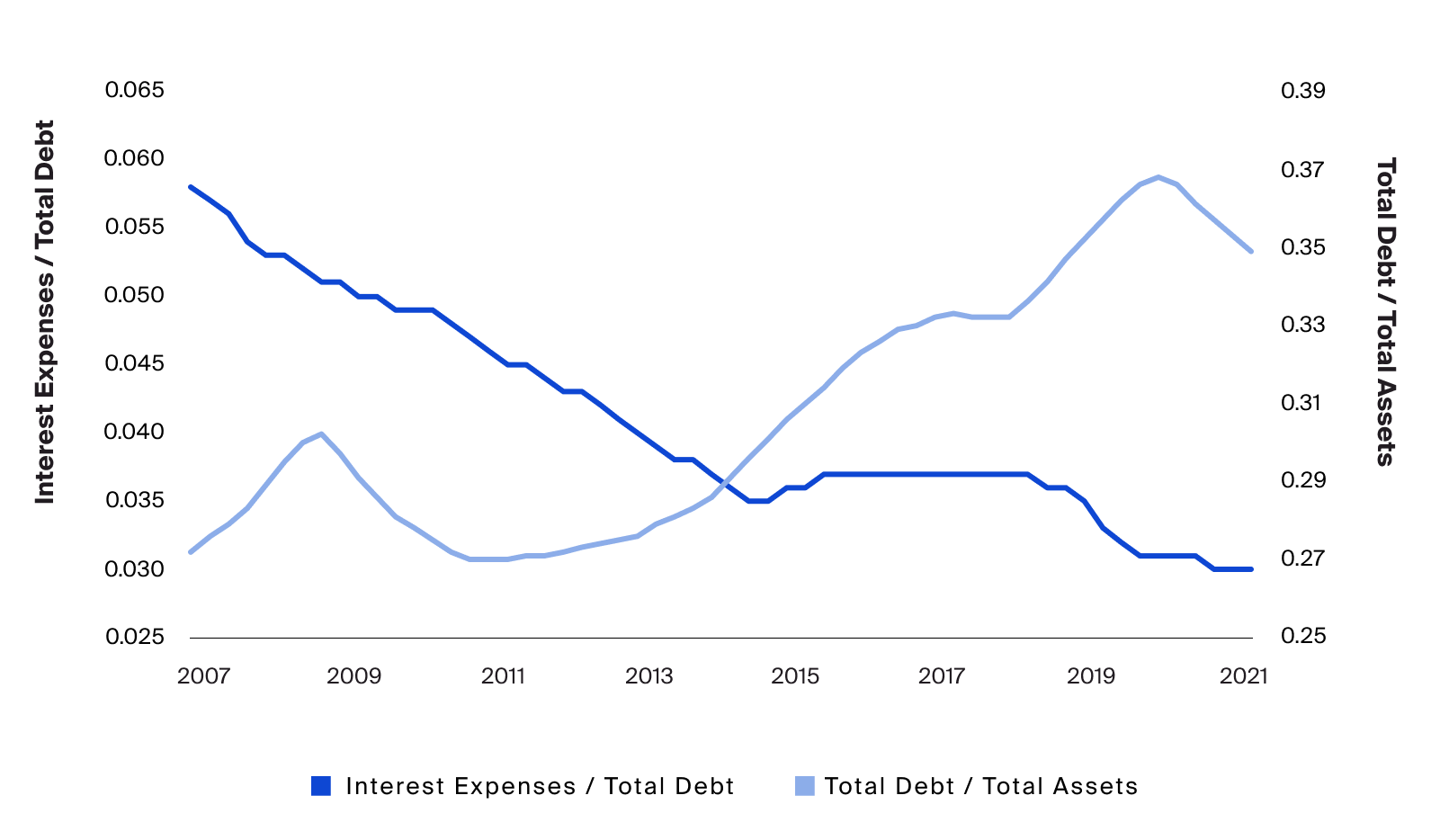

Like the credit-related signals we explored previously, the economic indicators discussed above suggest a bearish outlook for many companies as they aim to maintain margins. A key issue here is that corporate leverage at the individual company level has increased substantially since the GFC (Exhibit 2). During this period, historically low interest rates—both risk-free and spreads7—seemed to compel companies to finance their operations with a larger and larger proportion of debt. By some estimates, companies in the S&P 500 increased their net debt by three times over the past decade, an increase of $2.5 trillion in leverage in those index constituents alone.8 Increasing leverage in this way appeared to contribute meaningfully to a lower weighted average cost of capital and higher profit margins during this easy money era. Companies that now have unsustainable capital structures may be tested in this current and challenging environment.

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Compustat; S&P Dow Jones Indices, Note. Aggregate values for S&P 500 nonfinancial firms, September 2022.

Like the credit-related signals we explored previously, the economic indicators discussed above suggest a bearish outlook for many companies as they aim to maintain margins. A key issue here is that corporate leverage at the individual company level has increased substantially since the GFC.

While consensus estimates for company growth are still positive for next year,9 a forthcoming recession or economic slowdown, along with lower anticipated demand for products and services, may mean a decline in corporate revenues. Along with this revenue decline, there could be additional profit margin compression as companies—particularly those that financed their operations with floating-rate loans—are forced to manage higher interest expenses. With a “successful” drop in the inflation rate, the more variable components of the Composite Pricing Index (goods) would be more likely to decelerate first, while the “stickier” components (wages and services) are more likely to stay fixed or drop more slowly.10 This discrepancy may potentially mean that even more profit margin pressure is on the horizon.

Falling revenues and compressed margins typically result in lower earnings11 and free cash flow.12 Without as much cash on hand, companies may be less able to fulfill their debt obligations, potentially leading them to restructure or raise additional capital. As evidenced by the record corporate bond issuance last year, many companies took advantage of the easy money era to strengthen their balance sheets and thus may have a buffer in the near term.13However, eventually, if they do need additional financing, the higher-rate, risk-off environment may make raising capital more difficult.

Credit Markets Are Bigger and Badder

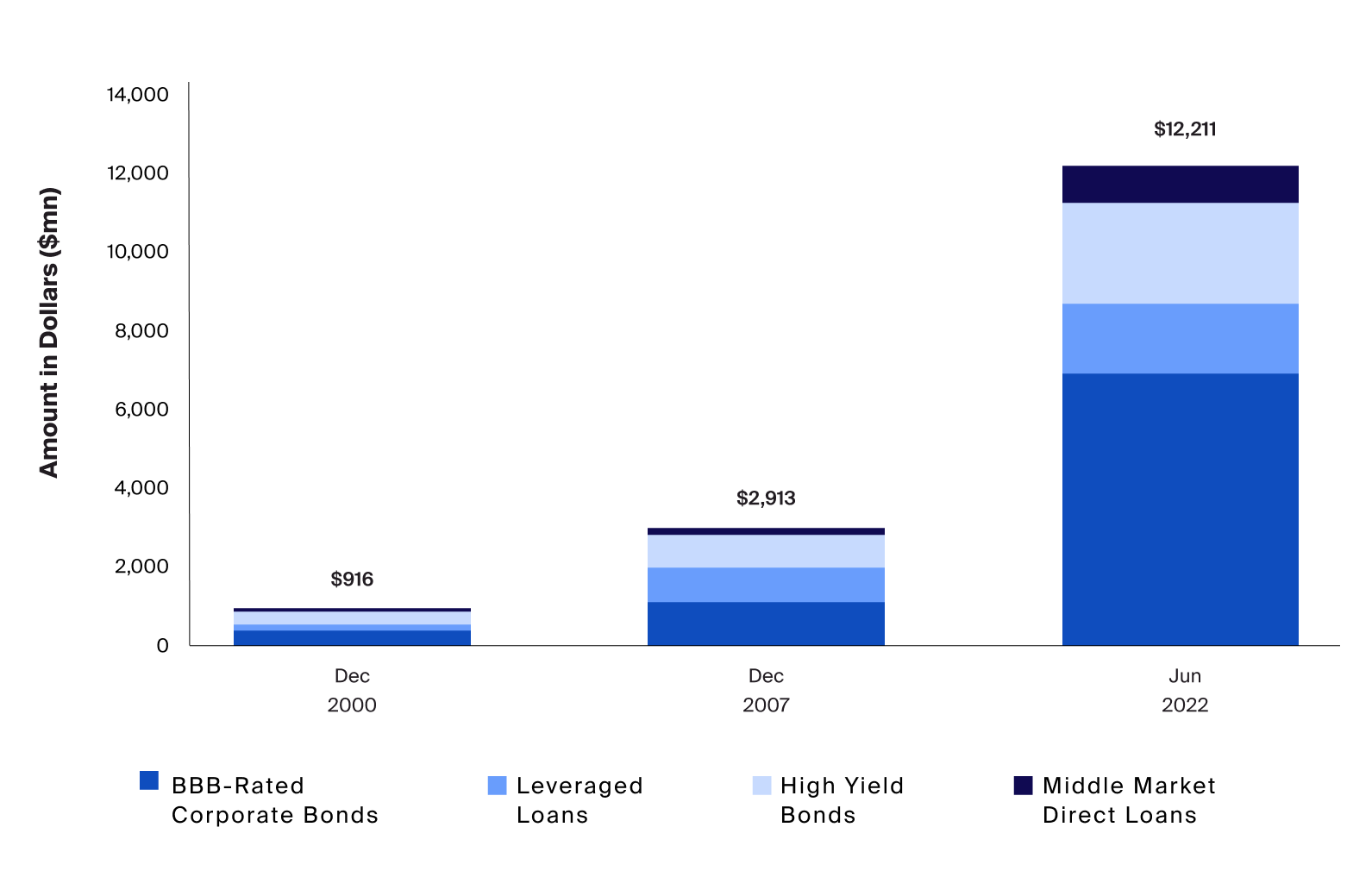

In parallel with the increased leverage on corporate balance sheets since the GFC, we may see added fragility from the abundance of low-rated global corporate debt that has accumulated during the same period (Exhibit 3). Advisors might remember the concern about the expansion of the so-called prospective “fallen angels” or “BBB cliff,” the latter named after S&P Global’s classification of the riskiest category of “investment-grade” debt,14 that had gained traction heading into 2020.15 A portion of this debt was pushed off the cliff in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic; however, thanks in part to the Fed’s more accommodative pandemic response, many of those once “fallen angels” have since recovered.16 According to JP Morgan strategists, an estimated $223 billion of ”fallen angels” downgraded in 2020. Since then, $48 billion of junk was upgraded to investment grade in 2021, with an additional $230 billion of ”rising stars” estimated in 2022, putting us nominally back to pre-COVID levels.17 We believe that the potential downgrade of these BBB-rated bonds may be reemerging as a potential issue. The thinking is that if these bonds are downgraded due to economic shocks or broader credit market changes like those we highlight above, the drop from “investment-grade” to “junk” could lead to an exaggerated technical price decline in the high-yield market that’s decoupled from fundamentals of the issuers.18 That decline might be exacerbated further as those same issuers—again, even those with decent fundamentals—experience potentially outsized increases in their cost of borrowing.19

Source: Oaktree Capital, as of September 2022.

In parallel with the increased leverage on corporate balance sheets since the GFC, we may see added fragility from the abundance of low-rated global corporate debt that has accumulated during the same period.

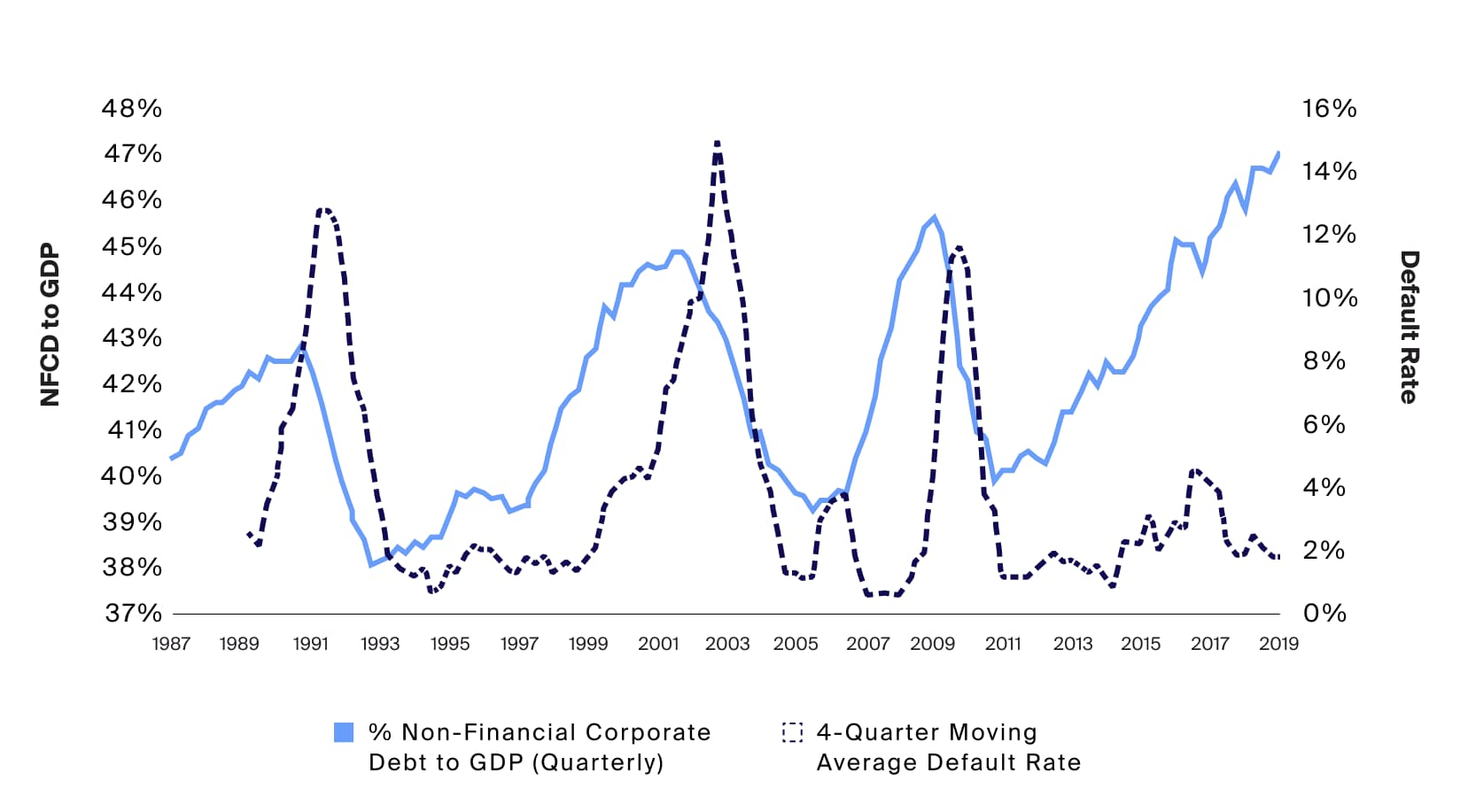

While we believe that ultra-low interest rates have helped to subdue corporate default rates since the GFC, we should note that defaults generally lag the economic cycle,20 which is only beginning to weaken in the United States. In the event of a recession, some Wall Street analysts expect default rates may climb to 5% by the end of 2023 and peak at 10.3% in 2024.21 However, defaults may take a while to rise in earnest, if at all, due to the relative strength of corporate and consumer balance sheets coming into this less-forgiving environment. Nevertheless, time still seems to be the potential enemy for companies operating with unsustainable debt levels.

Source: CFA Institute, as of August 2019.

Defaults may take a while to rise in earnest, if at all, due to the relative strength of corporate and consumer balance sheets coming into this less-forgiving environment. Nevertheless, time still seems to be the potential enemy for companies operating with unsustainable debt levels.

Dislocations May Be Here but More Distress May Take Time

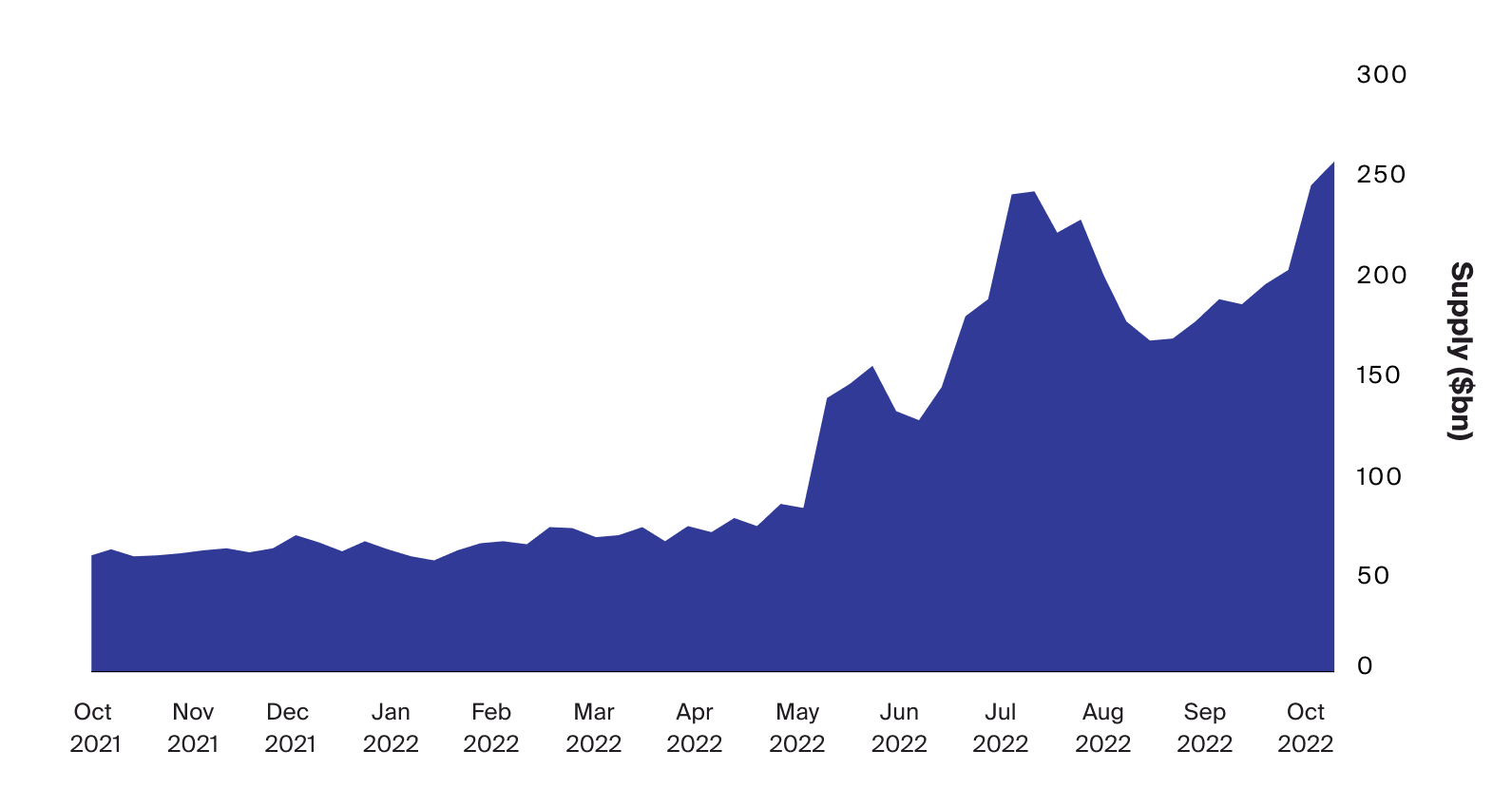

For distressed debt and opportunistic credit managers, this credit downturn presents a potential opportunity set that could shape up to be the largest and most prolonged since the GFC. As we mentioned in our last piece, the window of possible opportunity may be open for longer than previous dislocations given the Fed’s primary focus on inflation. Yet, taking advantage of such a window may require a nuanced and experienced approach.

Source: Bloomberg, Data compiled by Bloomberg, DDEBT G Index, as of 10/7/2022.

Footnotes

Note: Data includes corporate bonds trading at spreads greater than 1,000 basis points and loans trading below 80 cents on the dollar.

The window of possible opportunity may be open for longer than previous dislocations given the Fed’s primary focus on inflation. Yet, taking advantage of such a window may require a nuanced and experienced approach.

Many companies have strong balance sheets, and despite the Fed’s efforts, consumer demand has only just started to show signs of faltering, with the Michigan Retail Index falling below the critical 50-point mark for the first time since November 2020.22 Even so, over time, the downturn may stress individual companies and their related credit securities. In the middle market, we are already beginning to see an increasing dispersion of earnings performance by industry and company.23 That said, we do not believe that a broad sell-off is coming soon—instead, potential opportunities may likely emerge on a company-by-company basis. Near-term default risk is also likely to be low as many issuers took advantage of the low-rate environment to raise capital or refinance. As a result, there are relatively few maturities over the next 12 months.24 Indeed, companies still have runway today, but most will need to adapt to the changing environment.

The opportunity set may evolve differently for different sectors and different regions, with broader distress likely to come sooner for more vulnerable places like Europe,25 where companies face additional hardships of elevated energy prices, geopolitical shocks, and what appears to be the start of a deep recession.26

Considerations and Risks for Accessing Credit Opportunities

Given the complexity and ongoing evolution of the opportunity set, financial advisors who seek to take advantage of stressed and distressed credit opportunities may find it advisable to work with skilled and experienced credit managers. They should also be aware of the variety of strategies—such as bridge financing, specialty finance, and restructuring across public and private markets—that may offer access to this growing opportunity set.

There are also significant risks for financial advisors to consider when investing in any type of credit fund targeting this type of opportunity set. Investors risk permanent capital loss given the nature of providing capital to companies under duress or investing in stressed securities—in restructurings, creditors may receive only some, if any, of their capital back. Financial advisors may attempt to mitigate such risks by selecting managers that have the experience and internal resources required to appropriately respond to such complexities.

Additionally, any financial advisor interested in credit opportunities should carefully consider the potential benefits and drawbacks of allocating to different types of investment vehicles. Private credit drawdown funds, for example, have the potential advantage of deploying dry powder over a multiyear investment period. There are fewer legacy assets to contend with in a downturn, and capital can be deployed patiently. However, if the opportunity in stressed and distressed does not appear to the extent or duration that is currently indicated—for example, if the Fed backstops the economy after successfully combatting inflation sooner than anticipated—then a multiyear deployment may be a headwind to returns. As we saw with the COVID-19 credit downturn, dislocations can be short-lived. Conversely, deploying into an evergreen, credit-focused hedge fund that is already fully deployed may mean that capital allocated could be put to work more immediately. Though, fully deployed funds must contend with a legacy portfolio of potentially risky assets, exposing their investors to greater downside if issuers of the fund’s underlying credit securities experience even greater obstacles than originally anticipated—for example, due to a sharper-than-expected economic or sector downturn or higher-than-anticipated default rates.