Once considered by some to be “corporate raiders” who used junk-bond financing to take over companies, slashing spending and cutting workforce in an attempt to generate outsized returns, private equity has evolved.1

What You'll Learn

Analyzing value-creation drivers can foster a better understanding of private equity environments.

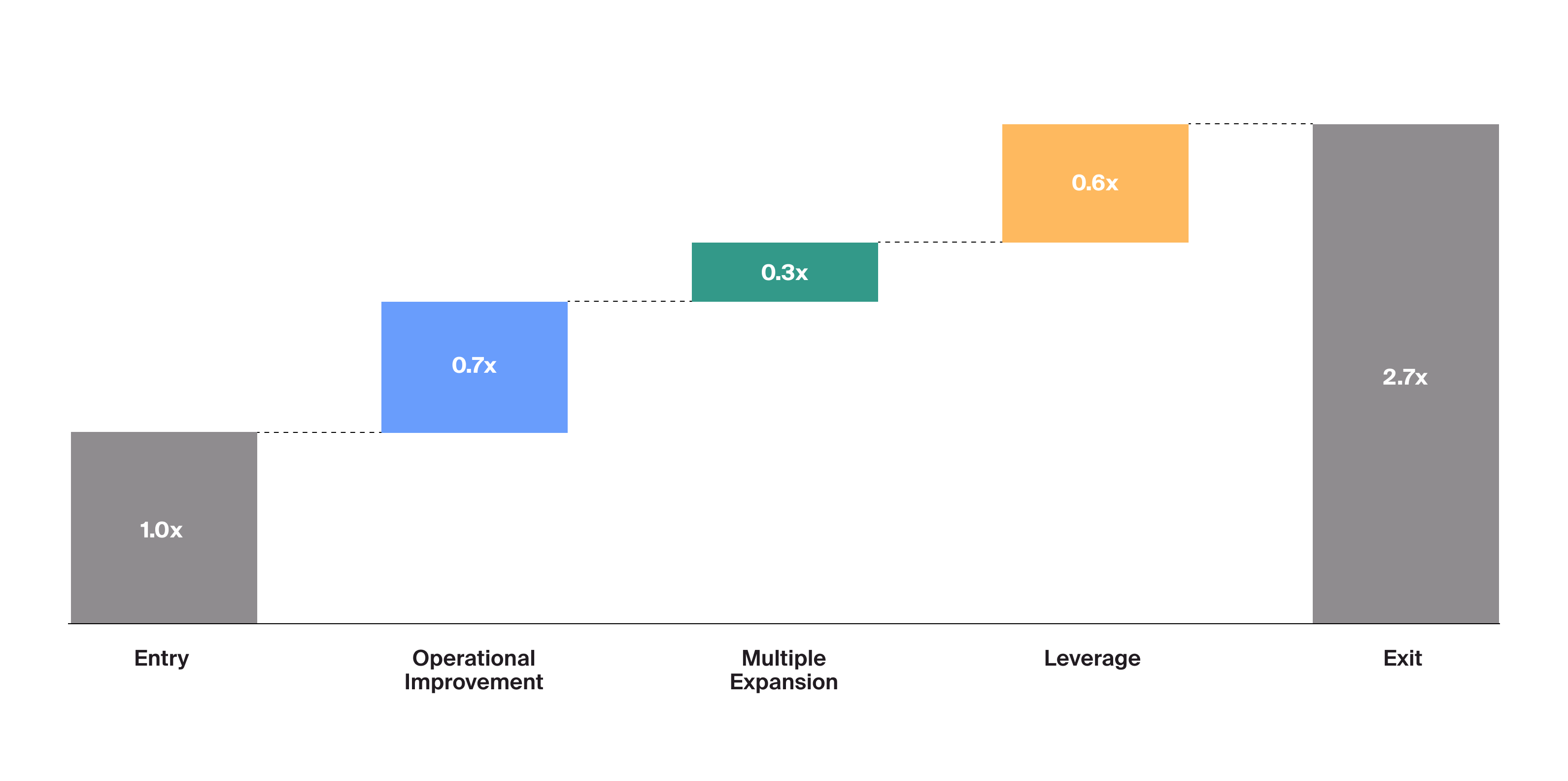

Leverage may no longer be the primary driver of private equity returns with its contribution to total value creation falling from 70% pre-2000 to just 25% post-2008.

Multiple expansion as a contributor to returns has historically varied and may be difficult to project, but lower entry points appeared to have an important impact. Managers can also attempt to contribute directly to multiple expansion through their actions.

Operational improvement appears to have been a consistent driver of returns and has become the largest contributor to total value creation—the experience and capacity to drive these value-unlocking changes may potentially be a key differentiator for private equity managers.

Deep manager diligence may be necessary to identify those managers with the experience to consistently implement value-accretive strategies for their underlying portfolio companies.

Private equity managers appear to have actively contributed to the majority of the value creation that has delivered returns above the public markets.

As our analysis here aims to unpack, how private equity managers have driven value for their investors has changed over time as the industry has matured and managers have attempted to differentiate in an increasingly competitive environment.

As private equity has developed as an asset class through multiple market cycles, a variety of value creation strategies has emerged, going in and out of style and effectiveness. These strategies may focus on a portfolio company’s operations, capital structure, or governance—the combination of which may impact the company’s revenue, margins, cashflow, and ultimately, its valuation. Over time, as the private equity industry grew, certain strategies have become more commoditized;2 in other words, tactics that were once differentiators for an asset manager may have since lost their competitiveness.

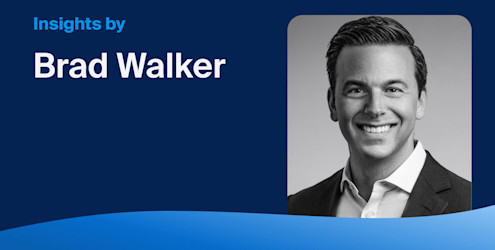

Understanding the drivers of value—and the manager attributes that may influence these drivers—can help financial advisors when selecting managers and seeking to target certain portfolio outcomes. In this piece, we offer advisors a deeper dive on a traditional value bridge based on novel deal-level research published by the Institute for Private Capital.3 This so-called “bridge” demonstrates three main categories of factors that appear to be driving value creation (Exhibit 1). By exploring the historical effect of each category, we aim to understand what, if any, influence private equity managers have had in the value creation of their portfolio companies.

What Are Some Main Drivers of Value in Private Equity?

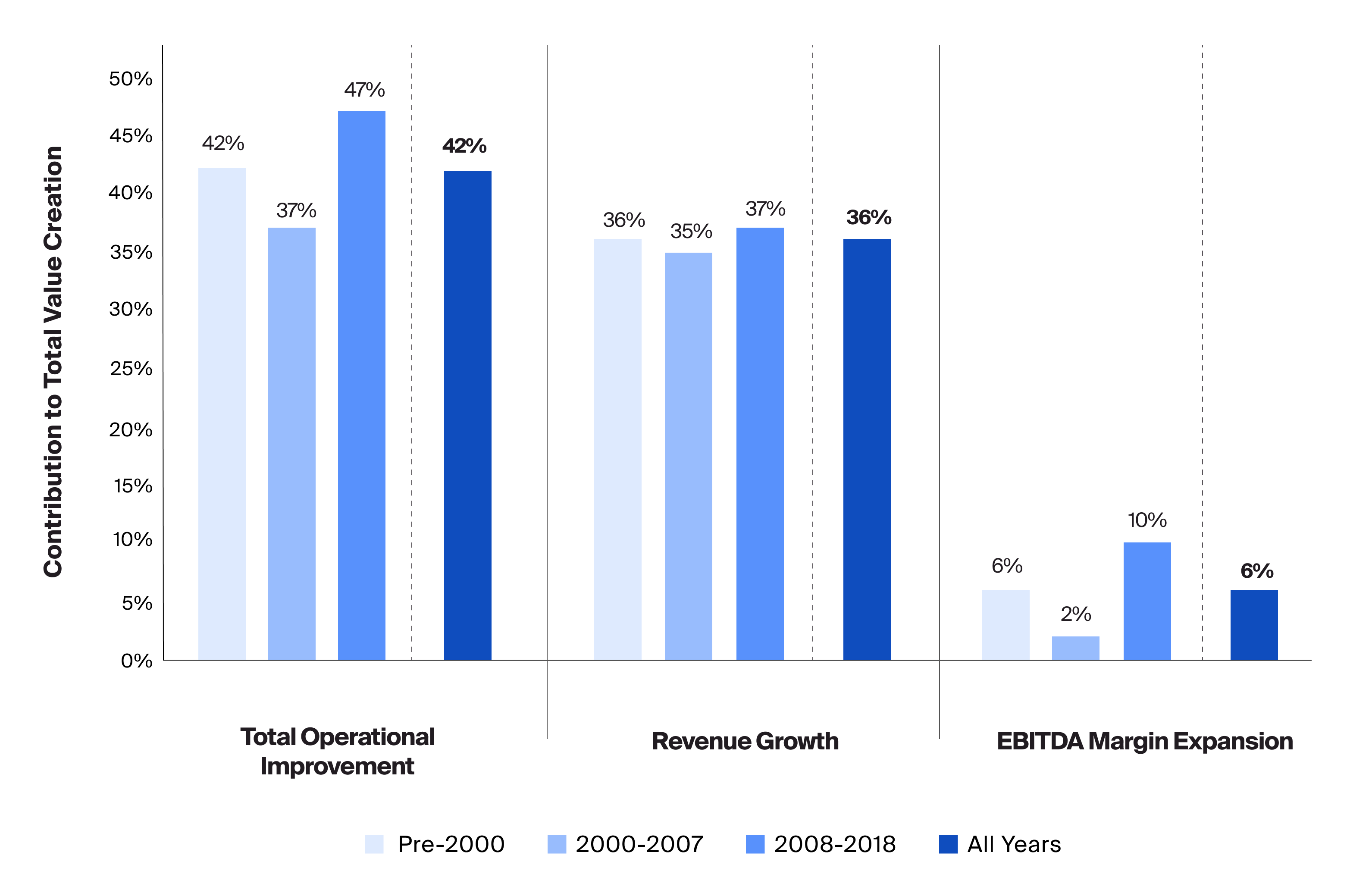

Though sometimes classified differently, value creation strategies in private equity typically fall within one of three main categories: operational improvement, multiple expansion, or leverage. As Exhibit 1 below shows, each has contributed to overall private equity value in varying amounts over the last three decades. A more nuanced assessment of these value drivers between 1984 and 2018 reveals how the private equity industry has changed, the potential relative importance of each factor, and how private equity managers have adapted in this increasingly challenging environment.

Source: Institute for Private Capital, Data sample includes 2,951 fully-exited deals from 1984 through 2018, with around $945 billion USD in combined equity investments and around $1.9 trillion USD in total enterprise value based on a Stepstone Group proprietary dataset of private transactions. "Pre-2000" is comprised of 272 deals from 1984 to 1999. "2000-2007" is comprised of 1,500 deals from 2000 to 2007. "2008-2018" is comprised of 1,179 deals from 2008-2018. As of January 2022.

Each has contributed to overall private equity value in varying amounts over the last three decades. A more nuanced assessment of these value drivers between 1984 and 2018 reveals how the private equity industry has changed, the potential relative importance of each factor, and how private equity managers have adapted in this increasingly challenging environment.

Leverage

Private equity is well known for its utilization of leverage. By securing debt financing for an acquisition, a manager can have greater purchasing power. And since the cost of debt is typically cheaper than the cost of equity, leverage can potentially amplify returns to equity holders. The interest paid on debt is also tax deductible, creating a tax shield that can increase the cash available to pay down debt or distribute to equity investors.

Over time, private equity managers typically pay down the debt used to finance the acquisition, which increases the value of the equity portion by reducing interest payments and increasing cash flow available to equity investors. The optimal amount of leverage is dependent on myriad factors, theoretically limited by the degree to which a company’s cash flows can service its debt.4

Advisors may rightfully question the extent to which the recently higher cost and lessened availability of debt financing has hindered this historically important driver. A higher cost of debt, all else equal, means a lower optimal degree of leverage that a company can take on. Nonetheless, leverage still appears to be value accretive in today’s market overall and may amplify returns—as long as the return on equity surpasses the cost of debt.5

Source: Institute for Private Capital, Data sample includes 2,951 fully-exited deals from 1984 through 2018, with around $945 billion USD in combined equity investments and around $1.9 trillion USD in total enterprise value based on a Stepstone Group proprietary dataset of private transactions. "Pre-2000" is comprised of 272 deals from 1984 to 1999. "2000-2007" is comprised of 1,500 deals from 2000 to 2007. "2008-2018" is comprised of 1,179 deals from 2008-2018. As of January 2022.

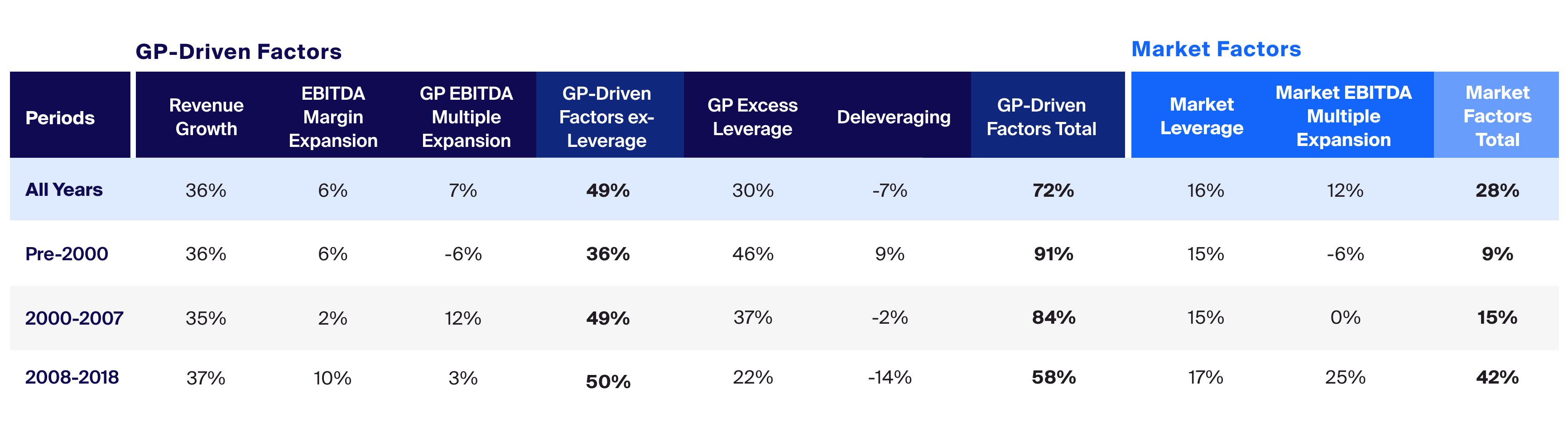

We compare the contribution to value creation of each of the three main drivers across three distinct eras in private equity: before the Dot-Com crash (1984-2000), before the global financial crisis or GFC (2000-2007) and post-GFC (2008-2018). When the private equity industry began gaining momentum, in the 1970s and 1980s, financial engineering was a main driver of returns. In deals completed between 1984-2000 in particular, 70% of total value creation was attributable to leverage alone.

In Exhibit 2 above, we compare the contribution to value creation of each of the three main drivers across three distinct eras in private equity: before the Dot-Com crash (1984-2000), before the global financial crisis or GFC (2000-2007) and post-GFC (2008-2018). When the private equity industry began gaining momentum, in the 1970s and 1980s, financial engineering was a main driver of returns. In deals completed between 1984-2000 (Exhibit 2) in particular, 70% of total value creation was attributable to leverage alone.

As capital and new entrants poured into this asset class, leverage became less influential. In the post-GFC era, leverage contributed to only 25% of total value creation, indicating far less reliance on financial engineering in today’s private equity strategies than in years past in generating returns. This may be surprising given the low interest rates that characterized most of the post-GFC period. In contrast, the average 10-year Treasury yield between 1984 to 2000 was 8.53%, compared to just 3.71% from 2008 to 2018.6

Given the asset class’s historical reliance on leverage, both rising rates7 and the post-GFC pullback in debt access have cast doubt around the prospects of private equity.8 However, the rise of the private debt market and managers’ gradually declining dependence on leverage in recent years could limit the effect of these particular headwinds.

Instead, managers may just need to be more selective, passing on companies that no longer meet their return hurdles and focusing on those with stronger balance sheets. Larger private equity managers have also employed all-cash deals, a buy-now, borrow-later trend to take advantage of opportunities where valuations have fallen.9 Assuming they can access more attractive pricing in the near term, managers might use this strategy to avoid being locked into expensive debt.10

Private equity's waning reliance on financial engineering, the emergence of creative financing strategies11 and adaptable playbooks12 may position the overall private equity industry for continued long-term growth despite the headwinds of the current environment.13

Multiple Expansion

Market multiple expansion can potentially be explained by three primary variables: multiple at entry, GP-led actions during ownership, and multiple at exit.

The multiple at entry can be thought of as the price paid for each dollar of EBITDA. Our analysis has indicated that while price paid is only one of three factors, entry point, as measured by the broader valuation environment, has historically contributed to better performance outcomes. Managers can invest committed capital over a finite, multi-year period and have varying degrees of pricing discipline, but ultimately private equity drawdown funds are beholden to the market environment in which they deploy capital.

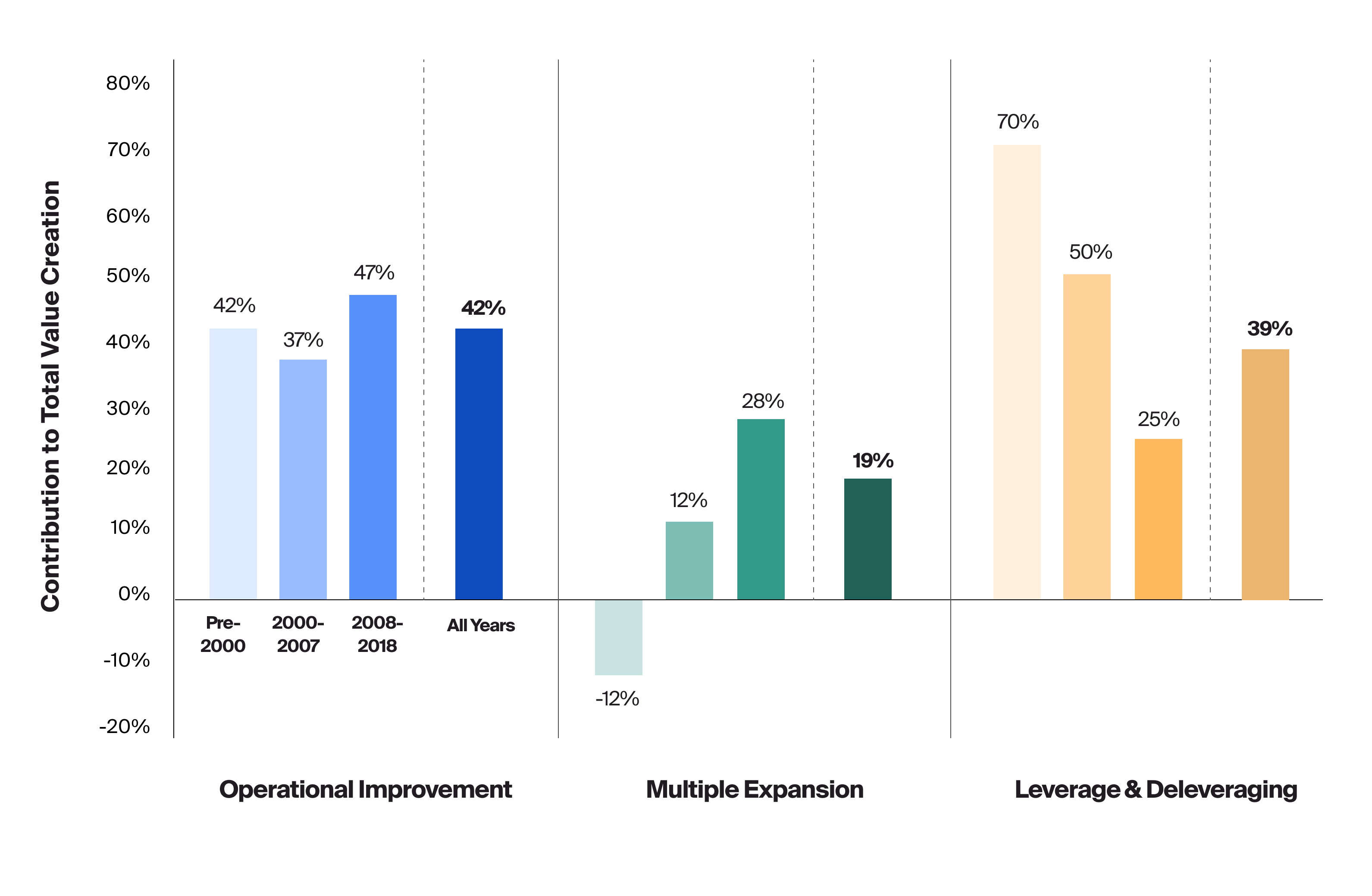

Multiples at exit may also depend largely on the market environment and as exits are several years in the future, may be difficult to predict. Market multiples may also compress more broadly, as was the case for the pre-2000 deals with market-attributable multiple compression contributing to -6% of total value creation. Conversely, the post-GFC period saw market multiple expansion contribute a positive 25% to total value creation (Exhibit 3).

Managers can, however, employ strategies to attempt to influence multiple expansion. Successfully implementing operational improvements, as described below, may increase a buyer’s willingness to pay a higher multiple. Managers may also seek to transform or grow existing elements of the business that are viewed more favorably and can command higher multiples than others. Lastly, managers’ ability to source more advantageously priced assets and exercise price discipline at purchase may also help contribute to above-market multiple expansion or mitigate market-wide multiple compression.14

Source: Institute for Private Capital, Data sample includes 2,951 fully-exited deals from 1984 through 2018, with around $945 billion USD in combined equity investments and around $1.9 trillion USD in total enterprise value based on a Stepstone Group proprietary dataset of private transactions. "Pre-2000" is comprised of 272 deals from 1984 to 1999. "2000-2007" is comprised of 1,500 deals from 2000 to 2007. "2008-2018" is comprised of 1,179 deals from 2008-2018. As of January 2022.

Multiples at exit may also depend largely on the market environment and as exits are several years in the future, may be difficult to predict. Market multiples may also compress more broadly, as was the case for the pre-2000 deals with market-attributable multiple compression contributing to -6% of total value creation. Conversely, the post-GFC period saw market multiple expansion contribute a positive 25% to total value creation

At the industry level, returns created through multiple expansion have historically been market driven. While margin expansion attributable to GPs contributed 12% to total value creation for deals conducted in the 2000-2007 period, pre-2000 deals experienced a contribution of -6%. Deals in the post-2008 period experienced a 3% contribution. Overall, the relative importance of margin expansion has varied, and in the pre-2000 era, it even detracted from total value creation.

Operational Improvement

With lower reliance on financial engineering to drive value creation over time, private equity managers have relied on other techniques to attempt to generate attractive returns for investors.

Operational improvement—the combination of growing revenues and expanding margins—has driven returns more consistently over time compared to leverage and multiple expansion (Exhibit 2). Such consistency may stem from the dependence of this factor on the GP rather than the market environment. In the most recent, post-GFC period, operational improvement was the top contributor to value creation. Of its two component factors, revenue growth historically contributed more to these gains.

Revenue growth can be driven organically or inorganically. Organic revenue growth strategies include improving sales of existing products or services to current customers, expanding the range of products or services, and entering new markets.

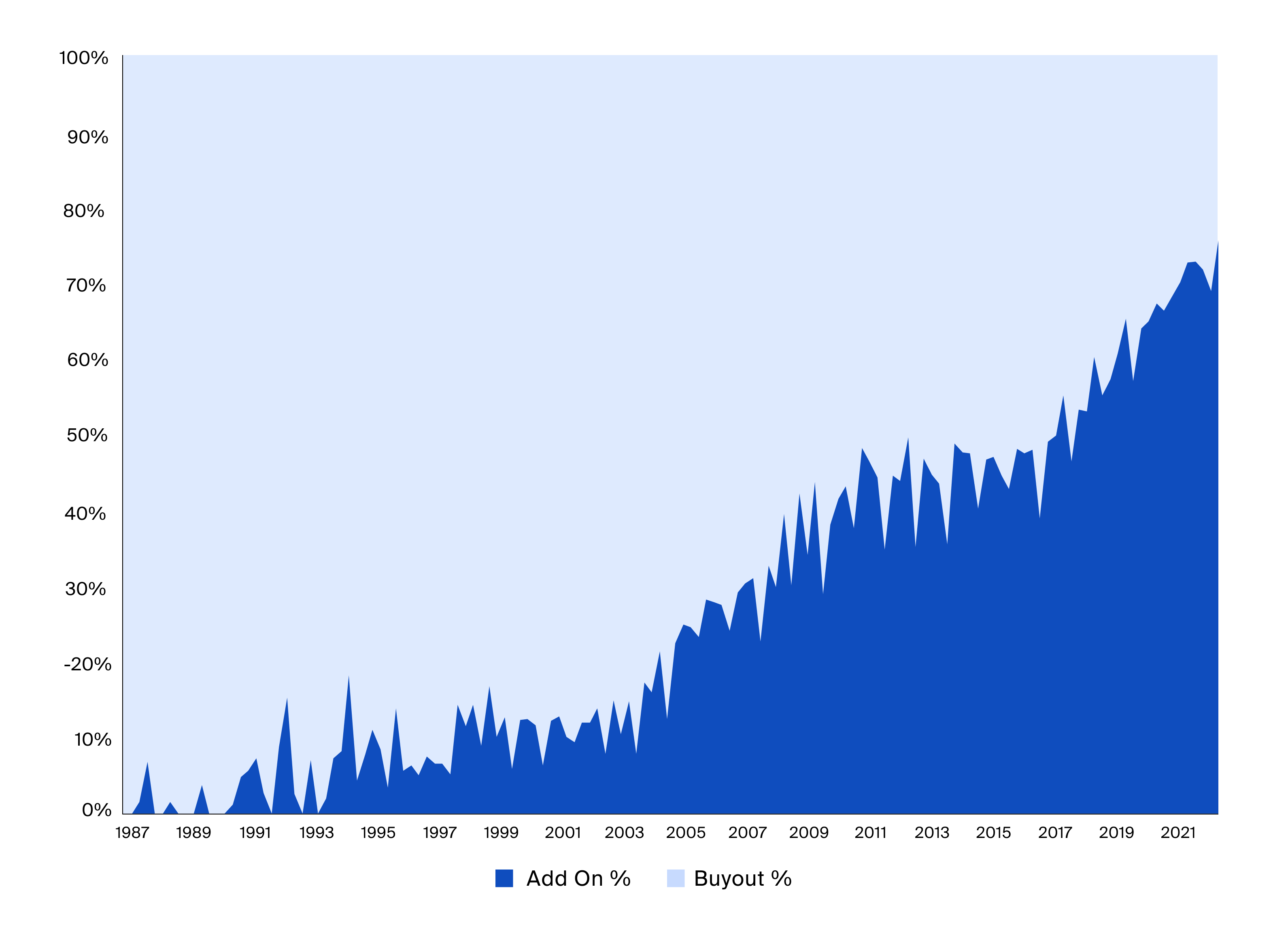

Inorganic growth strategies are often implemented through add-on acquisitions.15 In addition to providing revenue growth from access to new markets, customers, and products, acquisitions may introduce improved economies of scale between the combined entities that aim to reduce costs and improve margins. Larger businesses also typically sell for higher multiples, all else equal—a form of multiple arbitrage as the smaller company acquired and “added-on” will typically command a multiple at least as high as the acquiring company’s.16 The growth of add-ons over the past two decades is a testament to the benefits of the buy-and-build strategy (Exhibit 4). This approach may be particularly attractive in recessionary environments, as GPs can try to deploy dry powder in a way that improves portfolio company growth without assuming the risk of larger purchases.17

Source: Preqin, as of Q1 2023.

Larger businesses also typically sell for higher multiples, all else equal—a form of multiple arbitrage as the smaller company acquired and “added-on” will typically command a multiple at least as high as the acquiring company’s. The growth of add-ons over the past two decades is a testament to the benefits of the buy-and-build strategy

Margin expansion made a smaller but consistently positive contribution to total value creation across time periods (Exhibit 5). Strategies for driving EBITDA margin expansion broadly include cutting costs and integrating technology and automation, among other best practices that leverage a private equity manager’s industry experience, scale, access, and other resources to improve cost efficiency.18

Source: Institute for Private Capital, Data sample includes 2,951 fully-exited deals from 1984 through 2018, with around $945 billion USD in combined equity investments and around $1.9 trillion USD in total enterprise value based on a Stepstone Group proprietary dataset of private transactions. "Pre-2000" is comprised of 272 deals from 1984 to 1999. "2000-2007" is comprised of 1,500 deals from 2000 to 2007. "2008-2018" is comprised of 1,179 deals from 2008-2018. As of January 2022.

Margin expansion made a smaller but consistently positive contribution to total value creation across time periods.

Successfully improving acquired companies will most likely require managers to have specialized and deep industry expertise. As competition has increased, private equity professionals, managers, and funds have evolved from generalists to specialists in an attempt to differentiate themselves and generate higher returns than their peers.19

Given the importance of operational improvement to fund returns, assessing managers’ ability to make value-additive changes to portfolio companies is critical in manager diligence. An ability to deliver operational value has become a potential differentiator for GPs, especially in environments where using leverage may be more challenging.20

The Ongoing Role of Active Management in Private Equity

As an alternative asset class, private equity continues to evolve and adapt its strategies to aim to target above-public market returns throughout market cycles.21 Across all 2,951 deals between 1984 and 2018, 72% of value creation historically can be attributable to non-market factors, providing evidence of positive GP-related contributions.22

In the most recent period, the decrease in contribution to total value creation from GP-driven levers may be due to a mix of factors, including the outsized 25% contribution from multiple expansion, a decrease in excess leverage, and negative deleveraging—which was indicative of greater net debt remaining on portfolio company balance sheets at exit compared to prior periods (Exhibit 6).

Source: Institute for Private Capital, Data sample includes 2,951 fully-exited deals from 1984 through 2018, with around $945 billion USD in combined equity investments and around $1.9 trillion USD in total enterprise value based on a Stepstone Group proprietary dataset of private transactions. "Pre-2000" is comprised of 272 deals from 1984 to 1999. "2000-2007" is comprised of 1,500 deals from 2000 to 2007. "2008-2018" is comprised of 1,179 deals from 2008-2018. As of January 2022.

In the most recent period, the decrease in contribution to total value creation from GP-driven levers may be due to a mix of factors, including the outsized 25% contribution from multiple expansion, a decrease in excess leverage, and negative deleveraging—which was indicative of greater net debt remaining on portfolio company balance sheets at exit compared to prior periods.

Given the risks of investing in private equity funds, which include liquidity risk, market risk, business risk, J-curve effects, and others which we discuss in other articles, we believe that while the asset class may play a valuable part of a long-term growth-seeking allocation, careful manager selection and due diligence remain critical. Financial advisors would benefit from questioning both whether a given manager’s value creation strategy was successful in the past and whether any successful strategy might be repeatable moving forward, understanding that past performance is no guarantee of future results. An advisor might also consider the resilience and cyclicality of the sectors in which the manager intends to invest, along with the manager’s expertise investing in those sectors. Finally, because leverage can introduce additional risks, advisors should thoroughly grasp the role of debt in the manager’s approach.

Considering these risks has become even more urgent, as modern private equity managers’ ultimate success has seemingly become more dependent on the changes they effectuate for portfolio companies—beyond the use of leverage and independent of the market environment in which they’re buying, improving, and selling companies.

Other Considerations About Private Equity Value Creation

How do PE Companies Value Companies?

Private equity firms, typically use a blend of different metrics, insights, and knowledge to determine a company's valuation. That can include many types of information about a business, including:

Profitability

Top-Line Growth

Operational Efficiency

The Business’ Standing in Private Markets

Long-Term Value

Further, a company's location and where it operates can impact its value. For example, the metrics used to value a New York-based business vs. a European-based company might differ significantly.

Why Is Value Creation Important in Private Equity?

Value creation is at the heart of the private equity model. That’s why a PE firm’s goal is to increase the value of their portfolio companies throughout the holding period—but it may not be as easy as it sounds. In many cases, it requires the creation and execution of a solid value creation plan.

Further, they typically seek to to maximize all value creation levers that are available, like cost optimization, financial restructuring, marketing initiatives, improved customer experience, and more.

What's an Example of Private Equity Value Creation?

Suppose a New York PE firm dives into a healthcare startup. In that case, they may team up with the startup's current employees, managers, and executives to field ideas. Once they’ve gathered enough information, they may make value-adding suggestions like improving the supply chain, improving sales training, implementing generative AI, etc. If successful, the operational efficiency of the business may benefit which could result in an increase in certain performance measurements like profitability, which can become a significant factor in the determination of the startup’s valuation.

Is There a Formula for Equity Value Creation?

There's no universal "formula" for equity value creation in private equity. However, PE firms typically base their investment strategy on a blend of factors. This encompasses evaluating the company's current profitability, pinpointing areas ripe for optimization, and leveraging levers for operational efficiency.

ESG (Environmental, Social, Governance) considerations may also play a role in their decision-making process. The overarching goal is to amplify shareholder value throughout the investment's lifecycle. For instance, a buyout in the U.S. financial services sector might prioritize different initiatives than a tech startup backed by a platform like LinkedIn.

At its core, the formula generally intertwines strategic planning, diligent execution, and consistent monitoring.