Turmoil in US regional banks has appeared to accelerate the credit tightening that the Fed initiated last year with the fastest rate hikes in decades. While the duration and depth of the current regional banking crisis have yet to crystallize, advisors may be considering the potential implications of a potential credit crunch as banks pull back from lending and are forced to sell assets to improve balance sheet liquidity. What may be trouble for public credit could be a potential tailwind for private debt.

What you’ll learn:

A historic decline in bank deposits prompted by a growing differential between yields offered by checking and saving accounts and those of money market funds was likely catalyzed by the loss of confidence in bank deposits in the aftermath of bank collapses.

With liquidity in demand, private capital may have an opportunity to fill the void left by tightened lending practices at these banks.

A wall of maturing CRE debt could exacerbate ongoing credit availability issues, driving greater demand for private debt financing solutions from property owners with potentially better terms and pricing for lenders.

Banks also appear to be further retrenching from lending to corporations, giving direct lending strategies an additional opportunity to gain share in this environment.

As banks offload their riskier loans and other securities to shore up balance sheets, more opportunities may arise for stressed and distressed credit strategies.

Advisors and their clients considering private markets allocations should understand the key risks related to these opportunities, including credit risk, business risk, interest rate risk, and others.

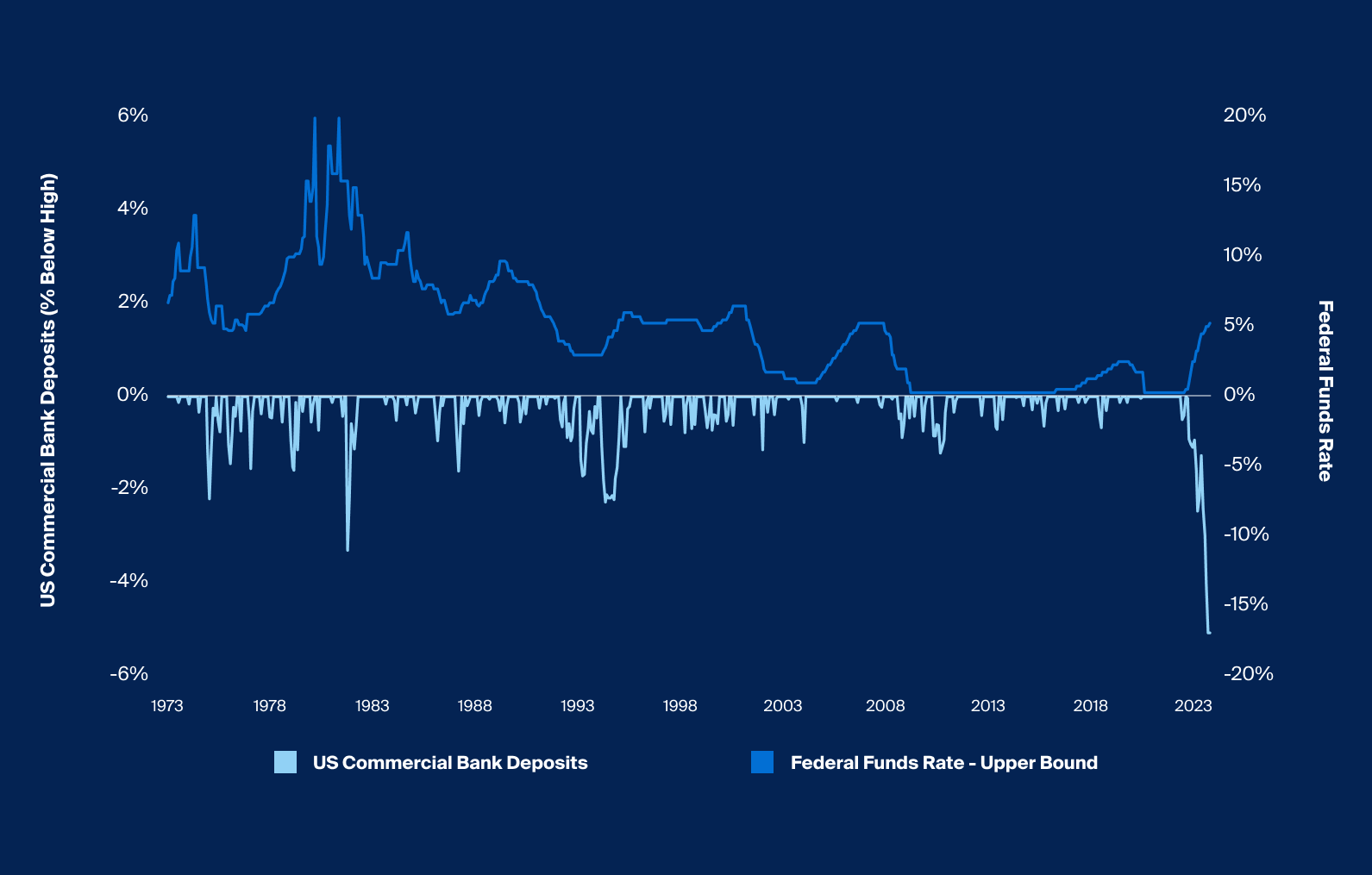

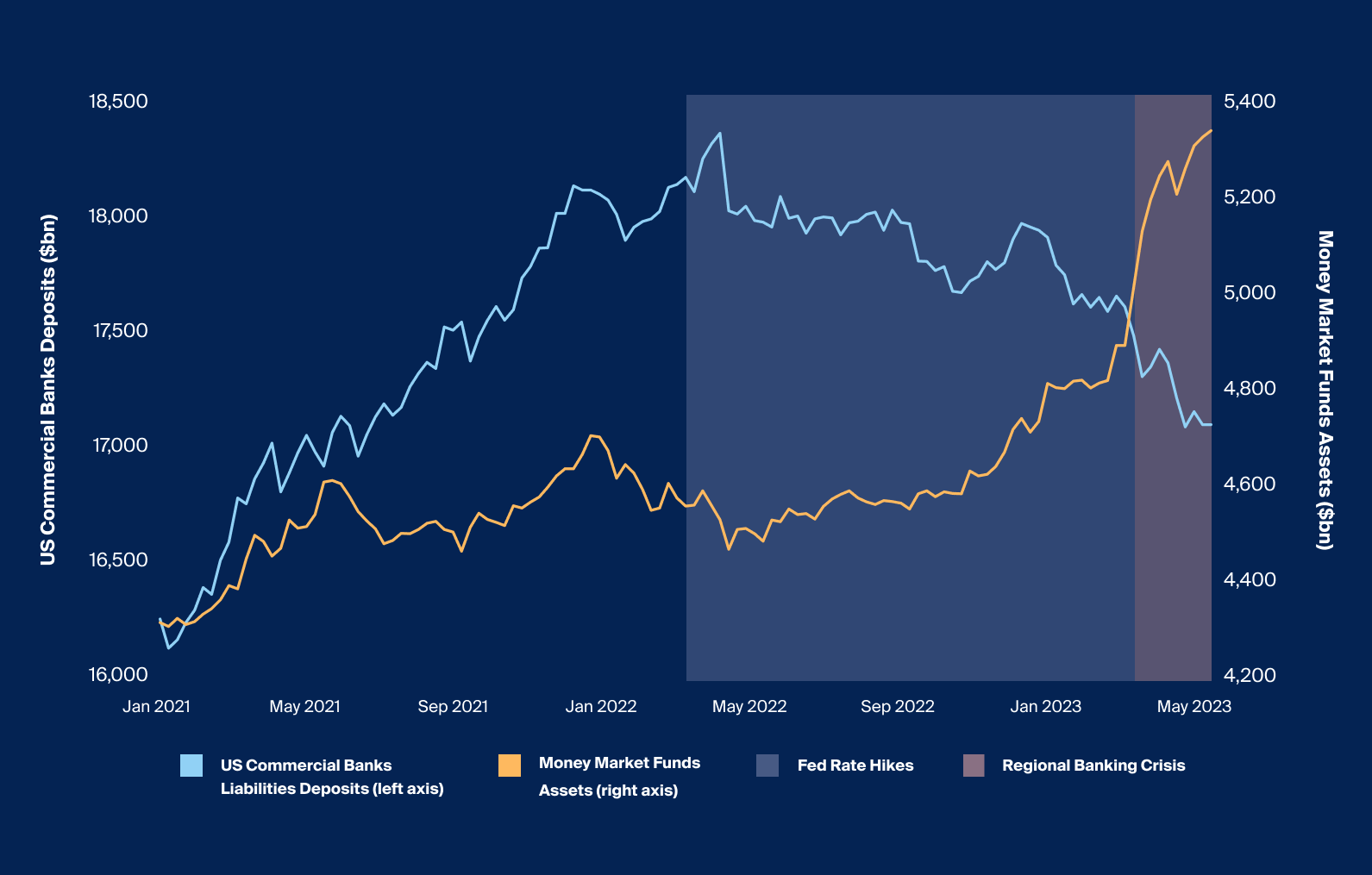

The outflow of cash from bank deposits began in earnest with rate hikes in March 2022 (Exhibit 1). We saw a rapidly growing differential between yield from short-term instruments like Treasury bills and checking and savings accounts at commercial banks.1 During the roughly year-long period, from the start of the rate hikes until the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, commercial bank deposits decreased $532 billion (Exhibit 2). But what began as a slow shift in pursuit of higher yield evolved into a flight to safety from regional banks.

Source: Bloomberg, US Commercial Banks Deposits represented by ALNLDEPO Index, % Below High is calculated as the percentage below the historical maximum value for total US Commercial Bank Deposits beginning January 31, 1973, as of 5/31/2023.

The outflow of cash from bank deposits began in earnest with rate hikes in March 2022.

In the 10 weeks from the SVB collapse to the time of writing on May 23, 2023, deposits across banks, large and small, have fallen an additional $455 billion (Exhibit 2). That rate of decrease in deposits is 4.5x the deposit outflow per week prior to SVB collapsing.

Source: Bloomberg, FRED, as of 4/30/2023.

During the roughly year-long period, from the start of the rate hikes until the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank, commercial bank deposits decreased $532 billion.

While rapid government intervention seems to have somewhat reassured bank depositors about the safety of their funds, the lure of money-market funds—yielding 5% or more2—may continue to pull deposits away from banks. In comparison, as of May 23, savings accounts still only paid 0.25% on average.3

Continued outflows appear to have disincentivized banks from expanding their loan books given their reliance on deposits as their primary source of funding. In good times, banks can typically rely on the stickiness of their deposits as they seek to profit from investing in long-term assets like loans. In situations where deposits are drawn down, banks generally seek to shore up balance sheets and improve liquidity to have the necessary funds to meet withdrawal requests and other obligations.

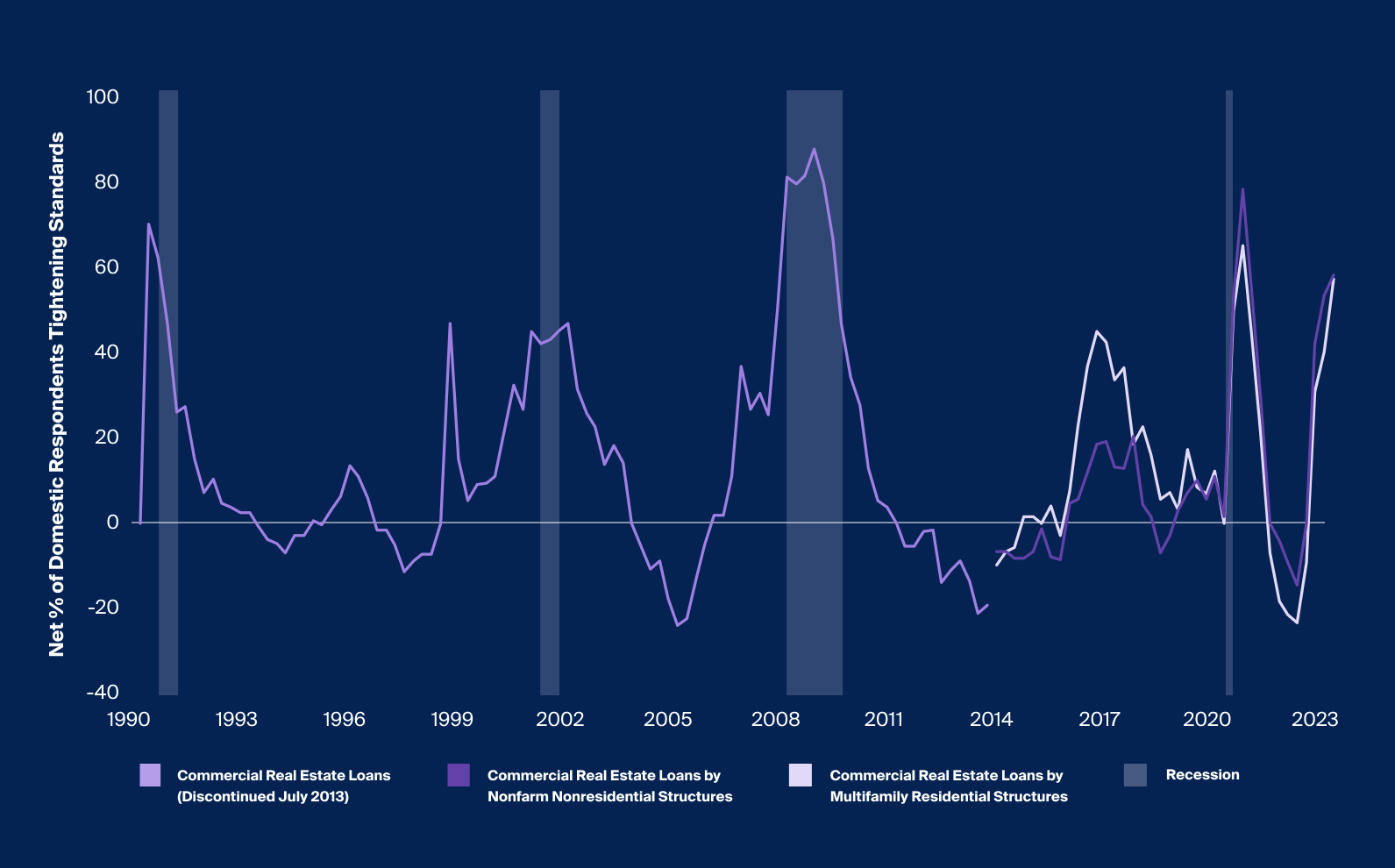

One such method is to reduce lending by tightening credit standards. As cited in the Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey (SLOOS) on Bank Lending Practices, as a result of the reasons listed above, in addition to bankers’ expectations for deterioration in the credit quality of their loan portfolios, we are seeing a degree of credit tightening only previously recorded in the run-up to or during the last four recessionary periods, as measured by the SLOOS.4 Regional banks may also face additional regulatory scrutiny and more stringent capital requirements as a result of recent events, which would cement this pullback from lending as a longer-term structural shift.5

Source: Bloomberg, Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey on Bank Lending Practices, as of 4/30/2023.

Continued outflows appear to have disincentivized banks from expanding their loan books given their reliance on deposits as their primary source of funding. In good times, banks can typically rely on the stickiness of their deposits as they seek to profit from investing in long-term assets like loans. In situations where deposits are drawn down, banks generally seek to shore up balance sheets and improve liquidity to have the necessary funds to meet withdrawal requests and other obligations.

Private debt funds may have an opportunity to fill a debt financing void in the areas where banks pull back lending. And these funds may do so with potentially more lender-friendly terms, lending to borrowers previously financed by banks or buying loans sold by banks seeking more immediate liquidity.6 The following sections highlight three major sectors where banks had previously played a significant role in financing or as buyers.

Commercial Real Estate

An estimated 40% of the $4.5 trillion US commercial real estate (CRE) mortgage market, backed by income-producing properties, is held by banks—70% of which are regional, like the few we’ve seen collapse this year. Smaller banks have much higher exposure to CRE from a balance sheet perspective, with CRE loans accounting for 20% of their total assets compared to only 4% at large banks. With regional banks under pressure, a major source of debt financing is being withdrawn from the market.7

Source: Bloomberg, Senior Loan Officer Opinion Survey on Bank Lending Practices, as of 4/30/2023.

An estimated 40% of the $4.5 trillion US commercial real estate (CRE) mortgage market, backed by income-producing properties, is held by banks—70% of which are regional, like the few we’ve seen collapse this year. Smaller banks have much higher exposure to CRE from a balance sheet perspective, with CRE loans accounting for 20% of their total assets compared to only 4% at large banks. With regional banks under pressure, a major source of debt financing is being withdrawn from the market.

A $1.5 trillion wall of CRE debt maturing within the next two years may exacerbate the issue.8 Given tightening credit availability from traditional bank lenders, property owners may be forced to turn to private debt solutions, pay down the debt with cash and increasing equity, or even turn over the keys to the bank if none of the other options are viable. Banks, which are not in the business of managing commercial properties, may, in turn, look to offload those assets at prices that would reflect the distressed nature of the sale.

Where there’s scarcity, there may be opportunity. Filling the debt financing void left behind by regional banks in commercial real estate means private lenders may be able to negotiate more protective loan terms and higher yields. They may also access a broader opportunity set of borrowers with potentially higher quality assets that were previously bank customers.9

Slowdown in CRE and regional bank issues may create a negative feedback loop given the close relationship between the two sectors. While both sectors are in better shape—banks are better capitalized with more backstops, and CRE is less levered—than during the era leading into the Global Financial Crisis,10 investors seeking exposure to the real estate sector may view debt as a more attractive risk-adjusted return than equity in the near-term. Debt holders have a meaningful equity cushion before valuation decreases would impair principal, and the yield commanded by real estate debt in the current environment compared to current cap rates may compel a closer look at this alternative investment strategy.11

Direct Lending to Corporates

Banks have also been pulling back from lending to middle market companies (particularly from underwriting leveraged buyouts) ever since the regulatory changes following the Global Financial Crisis limited how many loans banks can keep on their balance sheets. Private debt as an asset class has grown in this vacuum, fueling a broader and still growing private market.12

Recent regional bank failures can potentially lead to even greater retrenchment of banks from lending to small and large businesses. Direct lenders may have an opportunity to capture additional share, benefiting from access to a wider set of opportunities that include high-quality borrowers traditionally financed by banks. The funds with dry powder to deploy may now be able to command better deal terms that provide greater downside risk mitigation and more attractive pricing.13

Dislocations and Distress

Banks with more urgent needs may seek to shed assets from their balance sheets to bolster liquidity. On top of FDIC-led sales of Signature Bank and SVB’s mortgage-backed securities portfolios with a face value of $114 billion, other regional banks facing liquidity issues may also be pressured to sell.14 Forced sales of this magnitude could pressure structured credit markets, potentially leading to wider, more attractive spreads and dislocations that could be taken advantage of by opportunistic credit managers.15 Regional banks are also selling portions of their loan portfolios.16

More broadly, bank tightening to the degree reported has often been a precursor to recessionary periods (Exhibit 3). Banks are a major provider of debt financing to many segments of the economy and thus play a critical role in economic growth. A credit crunch may be a catalyst and amplifier to the anticipated increase in stressed and distressed opportunities due to the historic rise in rates.

Assessing the Opportunities Ahead

Impact of tightening credit conditions may take time to realize in actual lending with a three-to-four-quarter lag according to a 2000 study by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.17 The study, which validates the SLOOS in its ability to predict slowdowns in commercial lending and output, underscores that a shock to credit standards, or a “credit crunch,” is typically characterized by abrupt tightening of lending and a much more gradual easing. Loan underwriting by banks follow a similar pattern, again with a lag.18 As such, the opportunities created by a bank tightening may result in tailwinds for the aforementioned strategies for some time.

Advisors and their clients considering private debt allocations should however understand the key risks, including the credit risk related to the borrower, market risk, interest rate risk, and business risk, especially in the case of corporate debt. Stressed and distressed debt strategies in particular may incur a greater degree of risk, and investors may risk permanent capital loss given the nature of providing capital to companies under duress or investing in stressed securities.